A game for life

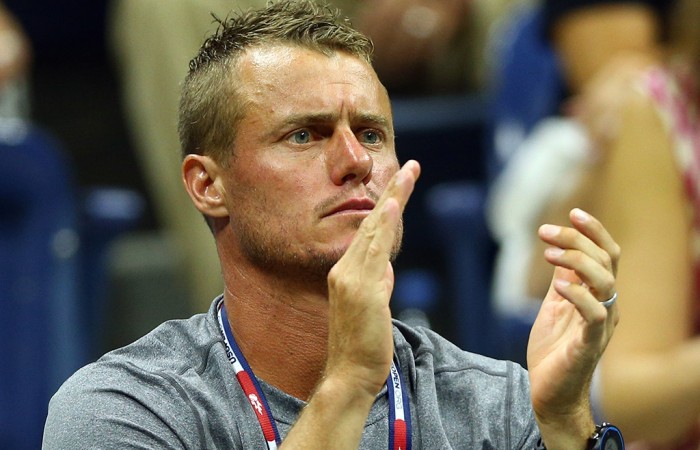

Fans need not wallow as Lleyton Hewitt leaves the professional game; not only will he retain a strong presence as Australia’s Davis Cup captain but his profound influence will also continue in other ways.

Melbourne VIC, Australia, 21 January 2016 | Leo Schlink

Time was when Lleyton Hewitt walked around Melbourne Park in complete anonymity.

In the late 1980s and early ’90s, Glynn and Cherilyn Hewitt would pack the family car each January and head east from Adelaide for the Australian Open.

The family ritual would include strolling to the courts from nearby accommodation and watching practice sessions before play started.

Even then, the younger Hewitts – Lleyton and his sister Jaslyn – were building encyclopaedic profiles of players.

By day’s end, the elder Hewitt’s would sometimes have to carry the sleeping kids back to their hotel.

As besotted as their children were with tennis, there was no suggestion of what would unfold: that Lleyton Hewitt would become a tennis lifer.

Tennis lifers are readily identified. Typically, passion, an appreciation for history of the sport and, regardless of the level of on-court competence, there is an incurable addiction.

Now 34, Hewitt is clearly a lifer.

His entire existence has been predicated on the sport.

His tennis journey initially revolved around outings at the Seaside Tennis Club, Memorial Drive and the family’s backyard court.

Unknown then to all but a small circle of South Australian sports, Hewitt was seemingly always clad in destiny.

From dreamer to prodigy to world championships, Grand Slam glories, the world No.1 ranking and a multitude of titles, Hewitt has coursed a rarely-trodden path.

With retirement looming at next month’s Australian Open, the next segment in the Hewitt odyssey has already been charted.

More than a quarter of a century on after first edging into public awareness, Hewitt will morph from Australia’s Davis Cup playing talisman to captain.

The transition is fluid, perhaps even seamless.

Once a rebel at odds with officialdom and sometimes opponents, the Hewitt of 2015 is a deservedly revered and battle-scarred warrior.

For the first time since he warred with older adversaries in club competition, when he was barely tall enough to peer over the net, Hewitt’s focus has switched from himself to contemporary prodigies.

Hewitt’s role now is to find, mould and harness talents to usurp him as Australia’s most recent male Grand Slam champion.

And given that Hewitt’s last major came at Wimbledon in 2002, the dimension of the task is clear.

Typically, dedication to task is the spur.

“I see my role as more of a mentor than a coach to these guys – they’re all going to have their own coaching situations, but I can be around and help them and understand their games inside out every single week,” he said on appointment as the Australian Davis Cup captain.

“I just want to have a really positive influence on their careers, and not just hopefully to win the Davis Cup but for them to get the most out of their potential, and hopefully win the Grand Slams.”

Indoctrinated as a teenager into the mores of Australian tennis lore, Hewitt was schooled in equal parts by John Newcombe and Tony Roche.

The famed pair, fittingly cast as Australian tennis godfathers, learned their trade under Harry Hopman, the master tactician responsible for the glories of the fifties, sixties and seventies.

Hopman had at his disposal a seemingly endless line of Grand Slam champions faithful to the Davis Cup call.

His successor Neale Fraser continued the legacy, winning the Cup on four occasions.

Eventually, however, the well ran dry.

When Newcombe and Roche took over in 1994, Australia was respected, but no longer feared. The pair outlined their vision to Hewitt, recognising kindred qualities in the fresh-faced young South Australian.

Like him, they are tennis lifers, too. Their mantra bit deep.

“I was fortunate enough to be around John Newcombe and Tony Roche,” Hewitt recalled. “They were two best of the guys in the captain-coach role that I could have learned from.

“Davis Cup meant so much to them. They wanted to put it back on the world stage, especially here in Australia. They had one goal of getting back the Davis Cup and I was fortunate enough as a 15-year-old to come up at that very time.

“The first tie as an orange boy I went to was when Pat (Rafter) came back from two sets to love down against Cedric Pioline at White City.

“It gave me goosebumps and I was doing everything in my absolute power to one day get a number on my gold jacket and be playing.

“And to think that I’ve been out there playing for 17–18 years in this great competition and representing Australia – you have your highest highs and your toughest lows in Davis Cup.

“The thrill of holding up these trophies is very hard to beat.”

Of all the eminent Australian tennis notables to have watched Hewitt’s progress from obscurity to the highest tennis coaching role in the land, Rafter has had one of the closest views.

Himself a former player and captain, Rafter first experienced the Hewitt dynamism when still approaching the apex of his own career.

Like Hewitt, Rafter is a dual Grand Slam champion and also a two-time runner-up at the highest level.

And while their personalities are polar opposites, Rafter – like Newcombe and Roche – instantly spied unmistakable qualities.

“He had something special,” Rafter recalled.

“I first saw him and played against him in Adelaide in 1997 and he was 15 and kicking my arse. I was thinking ‘This is not good.’

“I knew then there was something special about him and he came up to a couple of Davis Cup ties, one in Townsville.

“I just saw him every year and I thought ‘This kid’s going to be playing (Davis Cup) soon.’

“But he went to five or six ties without even playing. He was orange boy but he was part of that whole atmosphere and you could see how passionate he was.

“Once he got on the court in ’99 against Todd Martin and tore him apart in Boston was one of the most amazing things I’ve ever seen in Davis Cup, watching a young kid perform that way.

“We knew he had it.”

Rafter’s role as Director of Player Development at Tennis Australia presents myriad challenges.

Hewitt’s appetite for work and enthusiasm are not among them.

“We all know Lleyton’s history, it is remarkable,” Rafter said.

“With Lleyton taking over in Davis Cup, he brings a whole new level of passion. We’ve seen it so many times over the years. Some of the experiences I had playing in doubles with him Davis Cup were pretty amazing.

“The word you always use for Lleyton is passion and that has never waned throughout his whole career.

“Lleyton had Newk and Rochey when he first came on the scene and they instilled him that incredible tradition of Australian tennis.

“Lleyton took it all in. It was a big passion of his to win the Davis Cup. He wants to share that passion now with the guys coming through.

“Lleyton’s gonna give it his best shot, we know that.”

For those who watched Hewitt from the outset, there was never another way.

His father Glynn would often meet his son after junior competition at Memorial Drive in the expectation of a lengthy debrief of the match.

The debrief duly arrived – but it was often more about the swings and roundabouts of matches on adjoining courts.

The junior Hewitt, even then, had a burning curiosity about other players, other matches, other tournaments.

His attention now is squarely on Nick Kyrgios, Bernard Tomic, Sam Groth and Thanasi Kokkinakis.

“I’ll be doing a fair bit of travel with these guys and obviously helping them,” Hewitt said.

“I want the team environment to not only be Davis Cup weeks but be throughout the year, and I think that’s one thing that I can really bring to the table and help these guys, as long as they have the respect for me out there.”

That respect is surely guaranteed given not only his galvanising personality, but also a phenomenal career in Davis Cup.

Australia’s 89th Davis Cup representative finished his career in September as the nation’s most successful, with the Australian record for most ties (41), most years played (17), most total wins (58-20) and most singles wins (42-14).

He was a member of the winning teams in 1999 and 2003, and also appeared in the 2000 and 2001 finals.

So what will this tennis lifer bring as manager, mentor and confidante?

“Obviously, wearing your heart on your sleeve and going out there and committing yourself and giving 100 per cent every time you step on the court that’s what I’ve prided myself on and that’s what I’ll be bringing to the table,” he said.

“I’ve been fortunate enough to work under some of the greatest Davis Cup captains in history.

“We have a rich tradition in Davis Cup, with so many great players. I want the young boys to understand that, and I’m proud to have been trusted to lead the next generation. For me, it’s about instilling my experience and helping the younger players be their best.

“I can’t thank John Newcombe and Tony Roche enough for instilling in me the true beliefs of the history we have in Australian tennis and what it means to wear the gold jacket out there.

“For me, it’s all about instilling my experience in these young guys coming through and help them through not only the Davis Cup but all year round as well to help them become better players and to fulfil their potential.”

So, in a perfect piece of synergy and timing, Hewitt’s compass has been recalibrated.

The signature drive and ambition, ultimately sabotaged by injuries, still burns bright.

It now surfaces in a different form.

From talisman to tutor; magician to mentor, Hewitt’s enduring relationship with the sport continues.

He is a classic lifer.