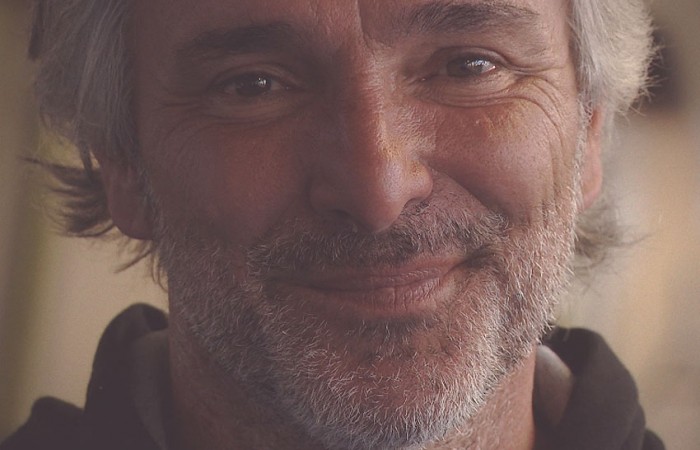

Jofre Porta: the man behind the champions

Meet Jofre Porta, the legendary Spanish coach who worked with champions Carlos Moya and Rafael Nadal and who is in Australia for a series of workshops.

Melbourne, Australia, 24 April 2013 | Matt Trollope

Perhaps a little unusually for a tennis coach, Jofre Porta says he lives for the process of developing elite tennis players over the spectacular results they may one day enjoy as a professional.

It was certainly the case when he guided Carlos Moya to the French Open title in 1998, and the world No.1 ranking a year later.

“I have a philosophy in my life, maybe it’s wrong or maybe it’s right. I don’t enjoy a lot the success, I enjoy more the work to arrive at the success,” the Spaniard explained.

“When I say that people think I’m pessimistic and I am a clown, but it’s true, I feel that. When he (Moya) won Roland Garros, I was in the box and it was amazing … but this (moment) was short, and the work is so long, so if you enjoy the work, you have more time for it (to be enjoyed).”

Porta was in Melbourne last week to share this philosophy, and many more, as part of an Australian tour in which he is speaking to hundreds of coaches about the environment required to faster develop tennis talent.

He draws on his experience from his role as director of the Global Tennis Team academy in Mallorca, a facility that develops players using unique coaching methodology and philosophies. Porta’s tennis background extends beyond the academy, including stints with the Spanish tennis federation, at Nike as an advisor, as a sports professor at the University of Valencia, and as a television commentator.

Porta began working with Moya when the now-retired Spaniard was around six years old, at the behest of Moya’s father, who asked that Porta watch his son play when the coach was working in Mallorca. Porta remembers a very shy yet polite child with long hair, who played “spectacular” tennis; it didn’t take long before he agreed to take on the prodigy.

“In this time I was young and I didn’t have any (major coaching) experience and we work together, we learn in the same time. We have a lot passion and we fight all the time, but really we don’t have a lot of knowledge. We start to invent things at this time,” he recalls.

Porta describes Moya as a Mallorcan sporting trailblazer, whose international success and fame spawned a generation of sporting stars from the Balearic island. Among those athletes is Rafael Nadal, another whose game was influenced by Porta in his formative years.

The coach came across a young Nadal while conducting a coaching clinic in Mallorca. Nadal’s uncle Toni urged Porta to see a young Rafa in action, who at that time was a right-hander with double-fisted groundstrokes on both wings. Porta began working with the “amazing” nine-year-old talent at his Mallorcan academy, with Nadal first attending three times a week – while still working with Toni as well – before living at the academy for one year.

Porta’s last tournament with seven-time French Open winner was at the 2004 Miami Masters, at which Nadal scored his first of many victories over Roger Federer.

“(With Rafa) I more worry about the technical things and the tactics but the real power of Nadal is the mentality, and that comes from working at home with Toni,” Porta said.

Nadal embodies many of the coaching principles adopted at the Global Tennis Team academy. One of these is “concentration”, which Porta believes is central to professional tennis success.

“When we speak about the discipline in Global – you are really focused all the time, really scared about everything – Nadal was like this. Nadal know everything that happened in every court, because his mind is going like animal,” he explained.

“When you are concentrated like this, your subconscious starts to look for a solution for everything … you don’t know why, but you know where the ball will go … be concentrated, and with that, you can get 90 per cent of the things in tennis.”

This is one of the many unique, if slightly unorthodox, approaches to player development at the academy.

There, tennis is considered as a “braking” sport, with Porta and his team less concerned with how quickly a player can get from point A to B than with how effectively they can stop and recover when forced onto the run. To build the requisite leg strength and fleetness of foot, players initially ditch their tennis racquets in favour of movement-based drills. When they do begin learning their strokes, they’re often double-handed on both sides, which Porta says limits their reach and thus requires them to better develop their court movement to track down balls.

“The legs in Spain is an obsession,” Porta revealed. “At Global, it’s double obsession.”

The veteran coach says that there are currently a handful of players at Global Tennis Team with extremely bright futures. Yet he is cautious when it comes to discussing this further.

“We never say we have fantastic players, because I think the humility is the only way to be a (good) person and player, and for that I prefer not to tell names,” he said.

“But we have some four or five people that we will try and start them as professionals.”

If those players turn out to be even half as successful as Moya and Nadal, then it will be yet another feather in Porta’s increasingly plumaged hat.

Find out more information about where Jofre Porta will be presenting as part of his “Creating environments to develop players faster” workshop series in Australia.